The following are a list of interview questions that were asked of us a while back and the answers that we gave. We feel that the responses help to illustrate some of the successes and barriers that are faced here in Malawi concerning the implementation of Permaculture principles.

How did you begin to be interested in Permaculture? What made you decide to develop your ideas?

In April of 1997, my wife, Stacia, and I were both sent to do HIV/AIDS prevention work in Malawi, Africa through the U.S. Peace Corps. Stacia is a Registered Dietitian, and I am a Social Worker. As we began our work, we visited various villages to orient ourselves to the areas in which we’d be working. In each of these villages, we asked the people what they viewed as their major problems. Not a single person at that time mentioned HIV or AIDS as being a problem, which was surprising to us considering that Malawi was supposed to be one of the top 10 countries in the world affected by the disease. Instead, people almost unanimously said that food security was their biggest problem.

At this time it was the dry season, so very little was growing and the landscape was blackened by the annual burning of vegetation that occurs in many parts of Africa. We asked why people weren’t growing food and most people replied that water during this time of the year was a problem. As we looked around, however, we saw a lot of water resources that were being wasted. For example, many women would go in the morning to fetch water—which could be up to a kilometer away—and then they would use it once to wash dishes or clothes and discard the waste water on the bare swept soil around their house. Other places, such as the drainage areas around the bathing areas or the end of boreholes had standing water that was just stagnating and breeding mosquitoes. When we asked people about the possibility of using these water sources more productively in the annual production of food, many agreed that it was a possibility, but then would counter with the argument that “you would need to give me seeds and fertilizer”.

Neither one of us had a strong background in agriculture, but both of us had grown up with families that had small summer gardens. From this limited experience we were pretty sure that you could grow some food without having to purchase seeds—after all, where do seeds come from if not from nature? We were also fairly sure that a lot could be accomplished with out the purchase of fertilizer with the incorporation of things like compost and mulching. So we began to collect local seeds and try out some ideas in our yard while also doing research. Fortunately, we were stationed at an Agricultural Research Station that had a nice library. This is where we came across concepts such as organics, bio-intensive gardening, sustainable agriculture, and finally…Permaculture.

There was a small book in the library called the ‘Kitchen Garden Book‘ that was written by a lady in Malawi named June Walker. We decided to pay her a visit and this was one of the true turning points in our lives. Mrs. Walker and her husband were colonialists that had lived in Malawi for almost 50 years. About 15 years prior to our arrival, they purchased a plot of land along the shore of Lake Malawi. This land was steep, eroded, and seriously degraded from years of hillside farming. Nobody wanted this land any more because it had become unproductive. With the use of Permaculture principles such as water harvesting, contour swales, composting, mulching, and intercropping with “guilds” they successfully managed to turn it into a highly productive area that resembles a tropical rainforest. Now there are fruits in every season of the year, vegetables and salad fixings any time you feel like a refreshing meal, legumes and staple crops such as yams and sweet potatoes abound, and there’s even enough excess to make things like jams, chutneys, and wine. Seeing this “Garden of Eden” first-hand convinced us that Permaculture definitely can work in Malawi, so the day we returned to our house we began to experiment with these new ideas around our own house.

This experimentation gave us the confidence we needed to begin to teach others about this method of agriculture. This eventually evolved into a 12-day training course that we presented around the country and have now refined to allow for other requests, anything from introductory one-hour sessions or 3-day workshops to 5-day beginner courses. We also use our current house as a demonstration plot and train various groups on a monthly basis. All of our teaching incorporates Permaculture, nutrition, and the reduction and care of diseases (especially HIV/AIDS) in Malawi, all of which are becoming integral to sustainability of the country.

What were the reactions of the villagers as you tried out your methods on their swept soil?

Teaching about Permaculture is one of those things that’s overwhelmingly satisfying, challenging, and frustrating all at the same time. It’s the thing that has kept us in Malawi for 10 years and also has us pulling our hair out at times. Malawi is at the point where the concepts of Permaculture are eagerly being received by many people. Modern agriculture combined with the continued slash and burn method of clearing the land and the resulting erosion has devastated the soil fertility of the country. Chemical fertilizer is currently the only thing that is being used to compensate for this loss. Up until about 6 years ago, fertilizer prices were subsidized by the government. Once these subsidies were removed many farmers found themselves in the dilemma of not being able to afford the fertilizer but trying to grow maize on soil that could no longer sustain a harvestable crop. People had become so dependent on agricultural inputs that they had forgotten about natural methods of restoring health to the soil and to their crops.

As we teach about this, you can often see faces light up as people recognize the potential that the country has to solve its own problems and obtain food security on a year-round basis. These are the people where we focus our efforts. Unfortunately, it is not everybody. Many people are not ready to hear about the alternatives yet. A good example of this is the two people that have been employed by us since we arrived. One is a single lady with six children who helps us with some of the more time-consuming tasks around the house. The other is our night watchman. Both have worked with us for the same amount of time, but during this period have taken very different paths.

The woman has begun to use Permaculture around her house and saved so much money on fertilizer that she purchased a dining room set for her and her children. She has food throughout the year and now even teaches about Permaculture if we are not around when people come to the house. The watchman is a single man who takes care of two children. He has not taken to Permaculture at all and is constantly trying to obtain loans for fertilizer or take an advance to buy food for his family, and his food reserves run out each year before the next crop is harvested. This has come to be known as the “hungry season” in Malawi and affects many families on an annual basis. With Permaculture, there is no reason for this hungry season because Malawi is blessed with a twelve month growing season.

Other people are just so ingrained in the “way things are done” that any change is very difficult. One example is the sweeping that you mentioned. Around each house in the villages, the yards are swept down to bare dirt. The majority of soil nutrients are removed in this process, and the sun bakes this soil as hard as a brick. This makes it very difficult to establish any useful plants or tree crops near the homes. After one of our Permaculture trainings, one of the participants was so excited about the possibility of restoring the soil health around his house that he stated that he was going to go home and establish “anti-sweeping clubs”! When we ran into this person a few months later and inquired about the success of his clubs, he said that he couldn’t even get his own wife to stop sweeping, “She’s addicted” he said.

What’s the most common response that you get from the villagers who see what you have done?

This one really surprised me. At our demonstration plot we routinely take people around and show them the different things that are planted and the Permaculture principles that help them to grow. We tend to focus on the local food plants that Malawi has to offer since they are more adapted than introduced crops to Malawi’s growing conditions. Stacia has a list of over 500 edible plants that can be found throughout the country. At our last house we had over 150 of these foods growing on a year-round basis. As of a year and a half ago we moved to a new house and started over so we now probably have about 50-60 different local foods growing.

Many Malawians are very excited to see these foods that they remember eating in their youth, or remember their grandparents using, or maybe have never even heard of. They also get excited about the potential that Permaculture has to offer, but when we ask them why every village, house, or place of work can’t look like this, the most common answer is, “We Malawians are too lazy.” The first time I heard this I was so shocked I could hardly speak. Malawians are extremely hard working, and the current agricultural practices are so labor intensive that it borders on ridiculous. To farm and eat maize, it requires a family to spend several weeks preparing the field by digging ridges, then there’s the planting of the seed, the first fertilizer application, the first weeding, the second fertilizer application, the second weeding, the harvesting, the soaking, the milling, and the cooking. Not a lazy person’s choice of food by any means.

It seems that many people have been ingrained with and believe in this notion of laziness even though all signs point in the other direction. The bigger problem in my view is the lack of free thinking. The ability to try new things, experiment, and be creative seems to have been hindered during the 30 years of dictatorship. This translates into a fear of change and a reluctance to “break the mold”.

Stacia and I do the majority of our Permaculture ourselves without being full-time farmers. If anything, we are the lazy ones since once your “permanent systems” are in place they become less and less work each year. This means more time for laying in the hammock and drinking the homemade wine!

How do you respond to the Malawian farmers who don’t seem to believe that what you have done with your land is possible to do with their own?

This goes back to what I said earlier about not everybody being ready to adapt the lessons of Permaculture to their own lives. We don’t spend a lot of our energy on people who aren’t ready; we try to remain focused on the people who are interested, enthusiastic and willing to give it a try. When we do a training of 20 people, we expect about 3-4 people to be really excited about it and apply it at home and in their work, another 4-6 people who may try out a few of the ideas, and the rest to go home with little change. This may seem like low goals to set for yourself, but that one person who can really take these concepts to heart will be able to go home and influence a lot more people than we will ever be able to in a short training.

The flip side to this is that there are a lot of obstacles that need to be overcome before you can successfully teach people about Permaculture or get them to the point that they believe that it can work for them. First of all, there is a stigma surrounding the use of local foods. If villagers are using these plants then they are viewed as being “poor” or of being “bad farmers”. Instead of celebrating the abundance of resources that are available, many choose to ignore them and try to produce diets of introduced foods such as maize, cabbages, mustard greens, onions, and tomatoes. Secondly, there is an over-dependence on a single staple crop—maize—to meet the entire country’s annual need for food security. This puts people at risk in many ways. If the growing conditions are not favorable for this crop (which they often aren’t), then the harvests will not be sufficient to meet the demands of the population. Even when harvests are enough, a maize-based diet doesn’t provide all the nutrients that a person needs to remain healthy. When there is a poor growing season, donors are quick to rush in with foreign donations of more maize, further promoting the dependence on this one crop.

These are all things to take into consideration before saying that a person is or isn’t interested in the benefits of Permaculture. It is also important to teach about why it is important to the individual. In the past, many Malawian’s were told what to do but never why these things may be important to them. Noncompliance with these directives could result in grave consequences. For instance, there were forest plantations established in the north of the country that could have provided a lot of revenue, building supplies, and employment for that area, but the people that were involved with planting those trees were never convinced that they would receive the benefits from them. As a result, shortly after the dictator left office the forestry workers went on strike over an issue and burned the forest out of frustration. This was a lose-lose situation for everyone.

When we teach about Permaculture, we first try to show the importance of all the components such as nutrition and its relationship to the individual health, soil fertility and its relationship to reducing the dependency on expensive fertilizers, and even the importance of having food at your fingertips on a daily basis so as to eliminate the “hungry season’.

What has surprised you the most as your work has grown?

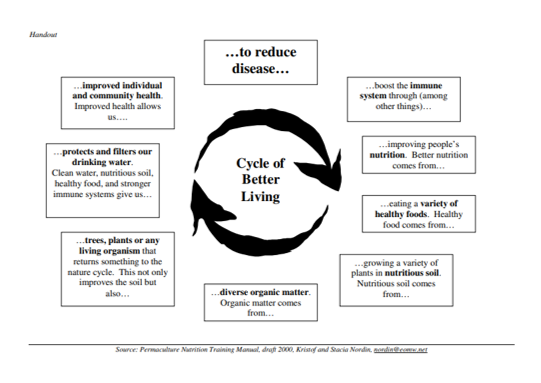

Probably the most surprising thing for me has been how much potential there is for Permaculture to assist with the problems that we see in Malawi, and how quickly this can be achieved. Permaculture is a holistic approach to living rather than just another agricultural system. This acknowledges that no problem or solution stands on its own. If we look at a simple problem like soil runoff, we see that it intensifies itself if left unchecked until a loss of soil nutrients become a eutrophication problem in a small river, and that small river becomes a potential for flooding when it joins the larger rivers, and those floods devastate houses, roads, crops, and infrastructure, and the resulting refuse that is washed into Lake Malawi ends up clogging the hydroelectric turbines and causing a power shortage for the entire country. People need to make the connections between the problems they face and the root causes of them, many of which are environmental and can be addressed with the application of Permaculture principles.

In terms of how quickly this can be achieved can be demonstrated by our current demonstration plot. Within six months of moving in we had more food established around our house than almost everyone in the area, many of whom have lived here for 10-15 years. Within one year we were giving tours for people to see what can be achieved with the use of Permaculture, and now at the year and a half mark we are already able to share excess foods and seeds with others. This type of potential is simply remarkable. Just imagine what would happen to food security and nutritional problems if every person in Malawi (11.5 million) even planted one fruit tree. This is not an unreasonable request, in the 10 years that Stacia and I have been here we have planted hundreds.

Why do you think that farmers keep buying expensive fertilizer when your method works better, provides a greater array of crops, is cheaper and is so easy? What can volunteers in the field do to create a change into more sustainable, organic agriculture?

One thing to keep in mind is that we don’t teach people to stop growing maize or stop using fertilizer. If people stopped using fertilizer when planting maize, in the first year there could be serious life or death consequences for that farmer and his/her family because the health of the soil is so bad. What we do teach is that with the incorporation of Permaculture principles, a person can start to reduce the amount of purchased fertilizer even within the first year. Perhaps after 5-7 years of intensive soil care that farmer may be able to rid themselves of the burden of fertilizer purchases. Currently, the soil in Malawi is too depleted to support the sudden withdrawal of chemical additives. The same goes for changing the current diet in Malawi, which is maize-based. We teach about the importance of reducing the amount of maize in the diet incorporating other foods instead and the nutritional impact on individual health, but we also know that behavior change takes time. We are all taught how and what to eat when we are very young. Our tastes for foods are also developed as we grow. If parents introduce their children to a wide variety of foods, then the chances are increased of that child growing up to eat a healthy and diverse diet. If we are taught to only eat one food day after day then the change to a healthier and more diverse diet will be a greater struggle, but one that can be achieved with determination and understanding.

The other answer to this first question is that many farmers are at a crossroads in Malawi, they are experiencing a great deal of problems but do not know where to turn for achievable alternatives. Agriculture Extension Workers are giving messages of how to obtain better yields with modern agricultural practices. This means more extensive mono-cropping, the purchase of new hybrids, the proper application of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and the elimination of all plants and insects that may be viewed as a threat or as competition. Children in the Malawian school system are also subjected to these messages in their agricultural studies. They don’t receive education on the hundreds of local food plants that are available, how to plant them, or even how to use them. This knowledge that used to be passed down generation after generation is now being left by the wayside, overshadowed by foreign influence and cultural stigma. Sometimes it is a much more complicated question than simply asking, “Why doesn’t everybody do it?”

In terms of volunteers in the field, it is important to keep stressing the same points over and over…VARIETY AND DIVERSITY! This is what it keeps coming back to. This is important for human nutrition, for soil health, for bio-diversity, for water management, for integrated pest management, for food security, for community health, and for the health of all the systems that we rely upon as humans. This is the way that nature provides for itself and it is the way that we need to start providing for ourselves if we want to have a chance of obtaining a sustainable future. I read recently that the bulk of the world’s calories now come from only about 20 plants. This places us all in a very dangerous predicament, if these crops should start to fail for any number of very plausible reasons, we will all be affected by the consequences of “putting all our eggs in one basket”?

The same goes for international development workers, the only thing I’d add is to take the time to find out about the local resources of the country in which you are working. Many well intentioned programs fail simply for this reason. Vast amounts of time and money often go into the development of programs that could have been avoided if local solutions had been sought.

An example of this lies in the approaches that have been taken in Malawi to combat vitamin A deficiency. The current approach at health centers is to issue children under five years of age with a small capsule of liquid that contains vitamin A. This capsule is given to the child’s parents with little or no explanation of where vitamin A can be found naturally. As a result, many people in Malawi now think that vitamin A can only be found at a health center. Other groups have been encouraging carrots which don’t grow well here, seldom produce any viable seed, and are not very familiar for use in the villages, but it’s the one high source of vitamin A that foreign development workers are familiar with so it is widely promoted.

There are so many sources of vitamin A in Malawian foods that it is difficult to see how there is any type of deficiency at all, but this just lends itself to the argument that lack of education and misguided programs are hindering true progress in this area. One of the simplest and cheapest ways to combat vitamin A deficiency would be to encourage people to grow and eat the foods that they know i.e. papayas, mangoes, guavas, passion fruit, pumpkins, dark green leafy vegetables, etc. Many of these foods are also great weaning foods for children under 5, and many also produce within one growing season.

Instead, the international development community is now seriously considering fortifying sugar with vitamin A. This not only goes against good nutritional advice by promoting the increased consumption of sugar, but it again lends itself to confusing the population about the true sources of vitamin A. This is only one example, but there are many more out there that would also serve to illustrate the importance and practicality of taking the time to learn about all of a country’s local resources.

How do you see the incorporation of Permaculture into Malawian culture affecting the nutrition and health of the citizens? Have you noticed any changes in the health of the farmers that have adopted Permaculture?

It’s interesting that you choose the word “culture” rather than “society”. Permaculture has a lot of implications on Malawian culture. In many ways it reflects the wisdom of the Malawian ancestors who survived for thousands of years without the assistance of aid agencies, NGOs, and foreign intervention. It also represents a time when farmers were able to meet food demands on a year-round basis without the need for expensive inputs and chemical fertilizer. According to a Malawian friend of ours who has a doctorate in agriculture, up until 1950 in Malawi’s entire recorded history there was only one year that mentioned any sort of food crisis. Now it has become an annual event. So what happened in those 50 years? Many people point to population growth as the main problem facing food security today. In my opinion, this simply means more hands to help grow things.

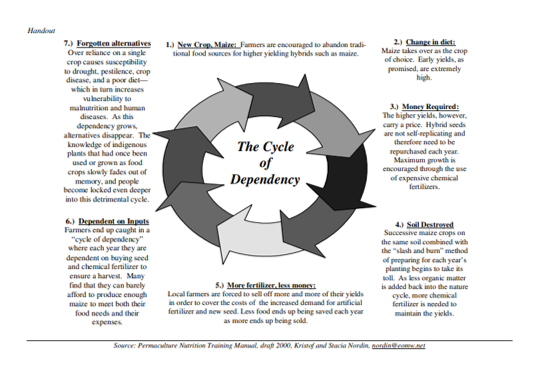

One of the major problems that has affected Malawian agriculture was the introduction of the Green Revolution. This so called “revolution”? was supposed to end all of the world’s hunger problems through the introduction of higher yielding hybrid crops. When hybridized maize came to Malawi many farmers adopted it as their staple of choice since the yield was much greater per plant than the traditional millets and sorghums that were being grown. Many farmers also started to clear away other traditional food crops to make room for the new “wonder” crop.

Unfortunately, many hybrid seeds cannot be saved and replanted the following year because the seeds tend to be sterile or lose some of their parent’s genetic traits. This meant that farmers now had to begin buying their seeds. Hybrid crops also tend to need heavy fertilizer applications to reach their true potential. This became another expense for the Malawian farmer who up until this time had become accustomed to no-to-low input agriculture. In order to meet the costs of this high input agriculture, the farmer sold the only thing he/she had to sell…their yields. This meant that the thatched silos that used to be full of staple crops now became quickly depleted to meet the expenses of that year’s harvest as well as the expenses for the following year. This plummeted the farmer into a cycle of dependency that ended up leaving them with less overall food than before the Green Revolution took hold. Note: We are currently hearing the same rhetoric about the “Genetic Revolution” being the new way to end world hunger. To quote Stacia: “Species don’t need to be improved; food production, processing, and consumption do.”

So, to come back to your question, the biggest area of impact that I have seen in the introduction of Permaculture in Malawi has been in helping to break this cycle of dependency and in giving options and alternatives back to the farmer. This has indeed had a significant impact on the nutrition and health of the farmers who choose to apply it. Many farmers are now realizing that they can have food all year long. This helps to eliminate the need for trying to store an entire year’s worth of food, it eliminates the need for trying to grow an entire year’s worth of food in a single 3-4 month rainy season, and it eliminates the “hungry season”.

Unfortunately, one of our biggest challenges in facilitating Permaculture and nutrition trainings is the lack of follow-up. We are often requested and funded to do trainings around the country, but are seldom funded to go back in 6 months to a year to see what those farmers are doing with the information. We know that good things are happening out there through the feedback from volunteers and even through letters from the participants themselves. As for the true impact of our work and its impact on community health, we have no base-line data from which to calculate any findings, nor do we have any means for which to collect such information.

Besides improving the soil quality and producing food, how else has your garden affected your community? How has the garden affected you and your physical and mental health?

A lot of people think that we are crazy. Permaculture tends to go against many of the current practices like sweeping the soil bare, hoeing up the grass, cutting down all the trees, and burning. To many, a yard full of trees, foods, and medicines seems unkempt or possibly a throw back to a time when the wild things ruled and an area could be full of dangers such as lions, leopards, and snakes. This is an image that we are trying to break. Once people start to see the world through the “eyes” of Permaculture, they start to see potential everywhere. Every inch of bare soil is a prospective sight for growing something useful to us as humans. We even use a lot of references to the Garden of Eden to help people see that ever since the beginning humans have associated the growth of a garden with beauty and paradise. The interesting thing is that once our demonstration plots have reached the point where we can do some landscaping, people actually begin to comment on how beautiful it is. It is only in the early stages when it seems untidy. In any case, our garden has definitely become a discussion point for the community. Even the people who tend to outwardly shun the ideas of Permaculture have been coming by our house to collect different seeds and medicines.

For Stacia and I personally, the garden represents a way for us to reconnect with an energy source that is greater than the sum of its parts. When teaching I liken it to singing in a choir. The choir has four parts: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. Each of these parts rehearses diligently until they know their place and role. But, it is only when all of these parts are put back together that something magical happens. These four parts all add up to a fifth unseen, unexplainable, and yet beautiful part that we usually refer to as “music”. This is the type of thing that we find in the garden. The more parts that are added, the more beautiful the music becomes.

Can you give us a brief description of how to start utilizing Permaculture in our own gardens and yards? Are there any websites or books that could assist someone who wants to become further involved?

When we teach about Permaculture, we always teach about the ‘concept’ of Permaculture rather than a set system of putting this plant next to this plant in order to maximize production. Permaculture is a system that works anywhere in the world. It is based on natural systems such as those you see in a forest. Your challenge is to find out what foods grow well where you are and start to set them up in a manner that mimics these natural systems, paying particular attention to the perennial plants (plants that will continue growing for several years). Start small and build up from there. Begin by considering all the components of the area with which you are working, i.e. soil fertility, water harvesting, sunlight, shade, etc. All of these things will help you determine the types of plants that you will choose. You wouldn’t put a cactus in a swamp, nor would you try to grow cranberries in a desert. These are the decisions that you can let nature help you make, what grows well in the conditions you have? Take a walk around, observe, learn, and share your findings with others. It’s amazing what a good teacher nature can be when we start to work with it rather than against it.

One of the main principles in Permaculture is that of a ‘guild’ With humans, a guild is any group of people that come together to work towards a common goal. It is the same with a guild in Permaculture, only in Permaculture it consists of different plants that help each other in one way or another. There are seven components of a good guild that you can keep in mind if trying to utilize Permaculture in your own gardens or yards. They are as follows:

- Food – Legumes and nuts, fruits, vegetables, staples, fats, and foods from animals

- Plants that feed the soil – Legumes and organic matter that provide nutrients to the soil

- Climbers – Important for making the most of available space because they grow vertically

- Supporters – Plants that provide support to climbers and other plants<

- Miners or diggers – Deep roots or tubers that open up the soil and/or bring minerals and nutrients to the surface

- Protectors – Plants that protect other things in the system (Repellents, attractors, live fencing, etc.

- Groundcovers – Protects soil, provides shade, holds moisture, and suppresses growth of plants which you don’t want (‘weeds’)

There is a great deal of information on Permaculture available to the public. Any web search will bring up thousands of references throughout the world. One of the founders of Permaculture, Bill Mollison, has put out some good resources. His “Global Gardener” video is one of special note. It shows how Permaculture can be adapted to different climates throughout the world. There are several books that can be found with an on-line search and contain good information for the beginning Permaculturalist. The following are a list of titles and resources that we have found useful:

- Introduction to Permaculture by Bill Mollison with Reny Mia Slay

- Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual by Bill Mollison (more advanced)

- Earth User’s Guide to Permaculture by Rosemary Morrow

- Getting Started in Permaculture by Ross and Jenny Mars

- In Grave Danger of Falling Food (video) by Bill Mollison

- Permaculture in a Nutshell by Patrick Whitefield

- Permanent Publications (magazine)

Where do you think the Permaculture movement is headed? What would you like to see happen in the future with Permaculture and developing nations? How do you and Stacia fit into the scheme?

here seems to be a global change in attitudes taking place towards environmental problems and their solutions. There are new types of sciences coming forward that are reflecting this change, things such as chaos theory, Gaia theory, fractal geometry, etc. People are beginning to realize that we rely on this planet for our survival much more than we realized in the past. Every component of life is important right down to the smallest bacteria. As we lose these elements of life because of the extinction that we are creating, a piece of us dies with them. Hopefully it’s not too late to make the necessary changes.

As far a Permaculture goes, I personally don’t care what you call it. Many people tend to get to hung up on labels and begin to miss the big picture. Permaculture has already begun to get a bad reputation from people that don’t understand it and have linked it to a cult-like following. This is easy to understand when you meet people who practice Permaculture and are so excited about something that actually works and at the same time improves the health of the individual and the environment. But Permaculture isn’t an “either/or” type of system, for instance either you use Permaculture or you destroy the environment. Permaculture is a set of principles that you can incorporate into your daily life, so whether it’s referred to as sustainable agriculture, organic farming, or simply being “environmental” it really doesn’t matter. What matters is that we all start to do something to make this a better place to live. Permaculture just seems to put it all together better than anything I’ve come across yet.

I would love to see Permaculture principles adapted throughout the world, not just in developing countries. The problems that we see in developing countries are often more apparent to the rest of the world because they haven’t had the money or resources to cover them up, but many of the problems that are being faced today are universal in nature and often even worse in so called “developed” countries. The prevalence of cancers and allergies in the United States, for instance, has reached epidemic proportions. This should be a sign to all of us that something is drastically wrong with the environment that we are living in and yet we continue to encourage corporate farming, create more waste than the rest of the world, and use all sorts of chemicals from cleaning agents to pesticides and dump many of them down our kitchen sink into our drinking water supply.

Permaculture could be incorporated into school curriculums and into city/municipal planning or zoning ordinances. It could be used by individual gardeners or commercial farmers, by community service clubs and churches. It could be a main component of all public areas including parks, reserves, or reservoirs. It could have a place in national policies and in the homes of families. It could be used to lessen the burden of hospital staff and it could be used to extend the quality of life for people. It could be used to create a sustainable future for generations to come or it could be ignored…it’s our choice.

As far as Stacia and I fitting into the scheme of things, we love what we are doing and we love living in Malawi. If that changes for some unforeseen reason, we would love to come back to the States and see where our passion for Permaculture can be put to use. Outside of that we are no more important or insignificant than any other component of this world that we live in.

What does your daughter think of the garden?

Nice of you to ask. Our daughter was born here in Malawi and has been raised in a traditional Malawian village, learning the local language of Chichewa and trying to carry things on her head. Her name is Khalidwe, which roughly translated means “what each of us bring to culture, our characteristics and traits”. Her middle name is Zikani, which means “firmly rooted”. We hope that both of these names will have significance to her as she grows and develops her world view. She has always been eager to learn about the garden and all of its components. Each day brings new opportunities to experience new and exciting things. It’s also fun for us to re-experience these things through her. When she was young, she spent a lot of time planting seeds with us and telling us what to put in the compost pile. In 2020, she completed her Permaculture Design Course (PDC), was certified, and is now studying in the U.K. in the field of Environmental Business.

What’s your favorite part of the garden or the gardening process?

For me here in Malawi that would have to be the rainy season. Throughout the dry season we water a few things, some things come into fruit while other things go dormant. When the rains come, however, its is literally an explosion of life. Plants, seeds, insects, birds, and animals all spring forth with renewed energy. The colors of the flowers unfolding are like watching fireworks in slow motion. Being surrounded by this type of energy is contagious, and people in general all seem happier and more content with life. That’s what it’s all about if you ask me.