In 1999 the Ministry of Education officially began a school meals programme to decrease absenteeism and to reduce drop-out rates. Almost every school is completely dependent upon outside resources to run the programme. In a 2003 survey of school meals programmes found that:

92 percent of the schools surveyed stated they are unable to continue school meals if donors pulled out.

School meals is just one part of a larger School Health and Nutrition (SHN) programme which was expanded in 2006. SHN requires a collaboration between Education, Agriculture and Health to succeed. There is a policy, strategy and guidelines to assure that everyone is clear on roles and goals.

From 2006-2011, Stacia Nordin, from Never Ending Food, worked with the German organization (GIZ) to help strengthen and build the capacity of the SHN program throughout Malawi. This post gives an overview of the beginning stages of the development process and provides you with some of the steps along the way highlighting a few successes and challenges. An update has been added in 2020 to provide you with links to organizations that have continued to work with Permaculture to sustain SHN.

Developing the Sustainable School Food & Nutrition programme:

In January 2006 the Ministry of Education, Science and Technolgy (MoEST) began to develop a school food programme that would benefit all schools and be able to be completely run by the MoEST and communities. A National Working Group of 19 people from all levels (headquarters, divisions, districts, schools and communities) worked together to explore current programmes around the world and learn from lessons already taking place in Malawi.

The overall goal is for teachers to physically implement the curriculum at the School with the learners.

A curriculum should be visible at the school, not something that remains as words on paper. Schools role model the curriculum while teaching it to the learners, providing a productive environment for learning. At the same time there are multiple benefits to the learners, teachers and parents through food production, improved natural environment and a calming environment for learning.

Sustainable Principles

- Sustain – to continue, to keep going, forever adapting

- Able – to be possible

In order for the programme to be sustainable, the National Working Group felt the following principles are important and should be followed in Malawi:

- Participatory process

- Commitment from all key partners at all levels

- Clear understanding all the concepts and technologies

- Using & sharing locally available resources

- Flexible and adaptable

- Messages are integrated and consistent with other sectors’ key messages.

To encourage sustainability, the emphasis is on low-input strategies that every school or community in Malawi can replicate using their own resources and without the need for additional outside funding. The responsibility for the long-term support for the project lies directly with MoE through integration of the ideas into the teacher and agricultural training systems.

Schools are the Leader right from the Beginning

It is expected that schools will need 1 and a half years of technical guidance to take them through a full cycle of seasons. The 1.5 years starts with the:

- School as the leader and

- Technical advisors stepping away slowly from the beginning

This is in contrast to what most development programmes do when they put the technical advisor as the leader at the start and then wait until the last month to ‘hand over’. In our case, the “Exit Strategy and Hand Over” start at the beginning.It took about 6 months to develop the programme which was termed the “Sustainable Food and Nutrition Programme” and based on Permaculture Design principles. The 2 main activities in the programme are:

- Increasing knowledge and skills in order to sustainably design and implement gardens, orchards and food programmes at the schools. Each school selects a community member, agricultural extension worker and teacher to be trained as Permaculture Facilitators, then their role is to assure that the programme is integrated into the whole school. In Permaculture fashion, knowledge sharing and continual learning by all is encouraged.

- Integrating lessons of sustainable nutrition, hygiene, sanitation, health, gender, HIV, economics, agriculture and the environment in a new, improved way of thinking and acting sustainably in all we do. Permaculture is integrated into lessons, practical activities and manual work. (Changes to the national curriculum are being worked on with the Malawi Institute of Education to assure that schools receive consistent, clear messages from all directions.)

The concept was approved by the MoEST for piloting and taken to District Executive Committees for feedback and interest in taking part in the pilot. The idea was enthusiastically received. Older people commented that this idea is not a new one, school gardens are something that used to happen in schools as part of agriculture lessons when they were children but faded away over the years. The difference between the past and the current programme is that it is integrated throughout the school system (school, community and agriculture extension) and across almost every subject and is built for sustainability and local control of the programme.

The timeline for the process is highlighted here:

Year 1 – 2006

- January – Started developing with National Working Group.

- July – Principle Secretary of Education approved

- September – Facilitators selected

- October – 28 facilitators trained. ~ 3 per Zone cluster

- November – Permaculture consultants work with individual schools 2 times a month

- In addition, all year key national partners worked with selected district partners to draft the first SHN strategy and guidelines.

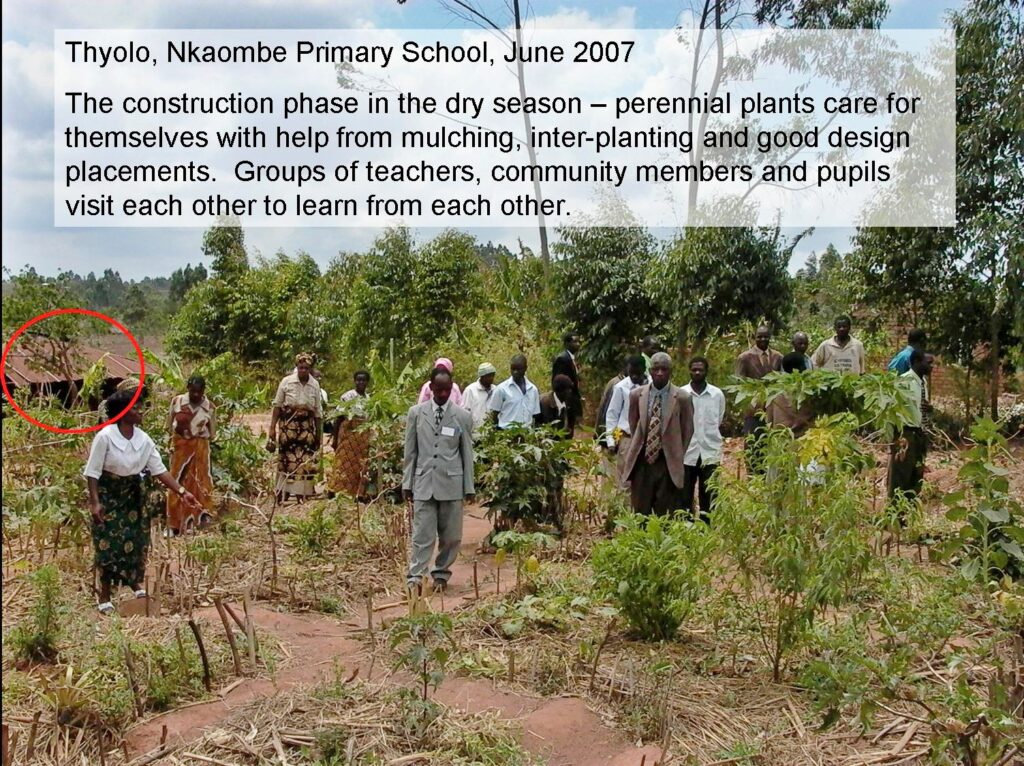

Year 2 – 2007

- January – National meetings suggest each school have 2 people fully trained

- February – More facilitators selected

- March – 145 facilitators trained / retrained ~ 3 per School

- June – Permaculture consultants work with individual school 1 time a month

- October – Permaculture consultants extended for another 6 months

- In addition, the SHN Strategy and guidelines progressed.

Year 3 – 2008

- April – Consultants finish 1.5 year contracts, government monitor schools. This is a very exciting and ambitious programme that the Government is undertaking, and it is currently being piloted until August 2008 in 8 of the 27 districts in 40 primary schools, 10 Teacher Development Centres, and 1 Teacher Training College (a total of 8 TTCs are in country).

- In addition, the SHN Strategy and guidelines progressed and were signed by all three ministries: Education, Agriculture and Health.

Year 4 & 5 – 2009-10

- Two additional years were added to strengthen work in the TTCs, national curriculum and work on monitoring school environment and student health. Results of these can be found in the dropbox link at the end of this post.

- The SHN guidelines and strategies were disseminated and discussed with all Districts.

Selecting Pilot Schools

Each school was selected through a sensitization process which stressed that there would be no handouts or inputs or incentives, that the incentive was improved food and nutrition security and an improved environment.

It was also stressed that the school would need to organize itself to get all the planning, implementation and monitoring done. No one would do it for them. Only technical knowledge and skills would be given. Schools that were not interested in this goal, or who had other critical problems at their schools were encouraged not to apply! It sounds a bit harsh, but with the level of dependency throughout Malawi, it was important to identify those who are truly interested, not those who were looking for allowances.

The following is a list of the initial pilot schools. If you are in Malawi, I encourage you to visit them by first letting the District Education Office staff know that you would like to visit. There is now a District School Health and Nutrition Coordinator in each district.

| Karonga 1. Lupaso 2. Malungo 3. Chinsebe 4. Masoko 5. Kasoba | Nkhata Bay 6. Ching’oma 7. Sanga 8. Chipuzumumba 9. Chilala 10. Maula | Lilongwe 11. Nankhonde 12. Chimwa 13. Malikha 14. Mataka 15. Chimwasongwe | Dedza 16. Maonde 17. Lobi 18. Chiphe 19. Chimwankhuku 20. Mphunzi |

| Zomba 21. Songani 22. Mpungulira 23. Naminga’zi 24. Nsondole 25. Katamba | Thyolo 26. Thunga 27. Namaona 28. Chinthebe 29. Wilson 30. Nkaombe | Mulanje 31. Ulongwe Model 32. Chisitu FP 33. Mulanje CCAP 34. Nalipiri JP 35. Ngolowera JP | Nsanje 36. Nyamadzere 37. Chikunkha 38. Nsanje Catholic 39. Mthawira 40. Mataka |

Results:

Some schools changed incredibly fast – while others moved more slowly, but the majority were right on track.

Successes

- All schools harvested something – some several times. Some schools eat the food, others share it, and others sell it and put the funds into the School Management Committee Fund.

- One school harvested enough food in the first few months to provide each of the 1,700 pupils a snack of ‘futali’ – a starchy root cooked with peanut flour.

- Another school had enough pumpkins so that the whole school had a pumpkin feast.

- Almost all schools are reduced their labor and increased productivity by changing the destructive habit of over-sweeping the dirt and burning organic matter to a better habit mulching and caring for plants, trees and animals.

- In the first 1.5 years, schools planted between 1,000 and 5,000 trees and other perennials and thousand more annual plants per school.

- All schools are at different levels of organization in terms of planning and coordination committees and work schedules to get the designing, planning and implementation structured in an independent and sustainable manner.

- Schools, homes, hospitals and other institutions surrounding the pilot schools are copying what the schools are doing – Learners at the school are proving to be an amazing way to spread positive messages back into their communities.

A few of the challenges

- Disagreements at the school, not related to the programme. If a school is not unified (or mostly unified) it is almost impossible to do any type of development at the school.

- People not managing their livestock – which is destructive to plants and trees, does not manage the manure efficiently and can be unhygienic with manure scattered everywhere.

- Lack of confidence from a long history of dependency. Some of the schools still thought that there were going to be ‘inputs’ or ‘food aid’ provided despite the lengthy and repeated sensitizations. This mentality slowed down the success at their schools.

The successes in the pilot well outweighed the challenges. Each of the challenges were addressed by the schools themselves and with unity, they are proving that anything is possible!

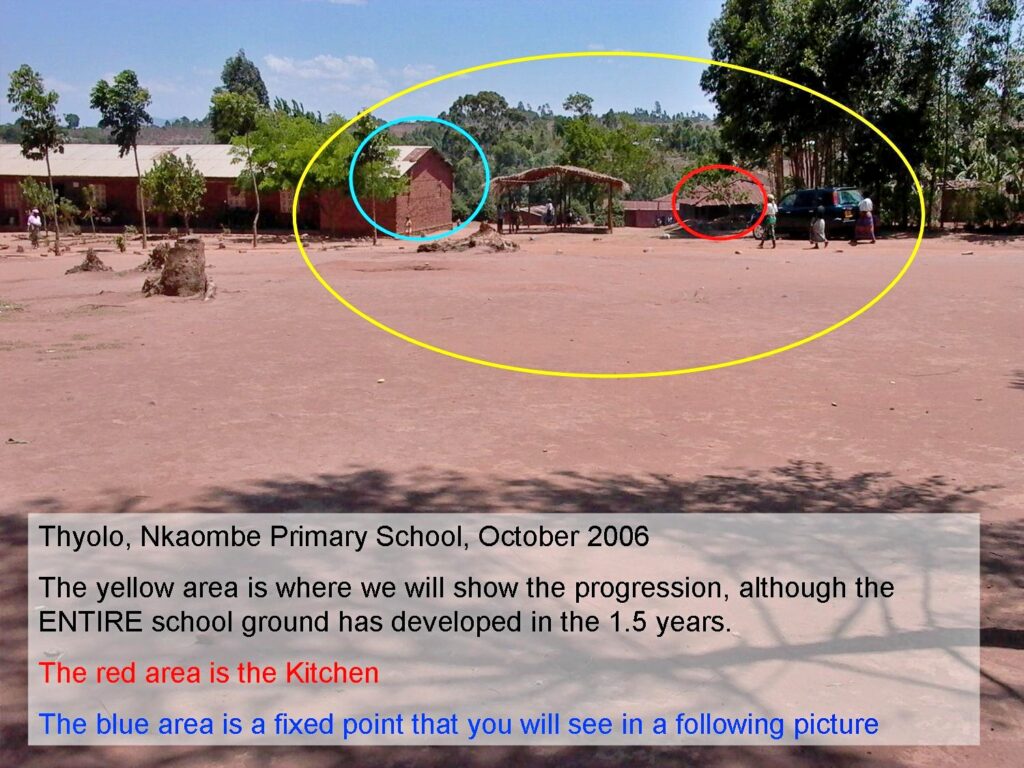

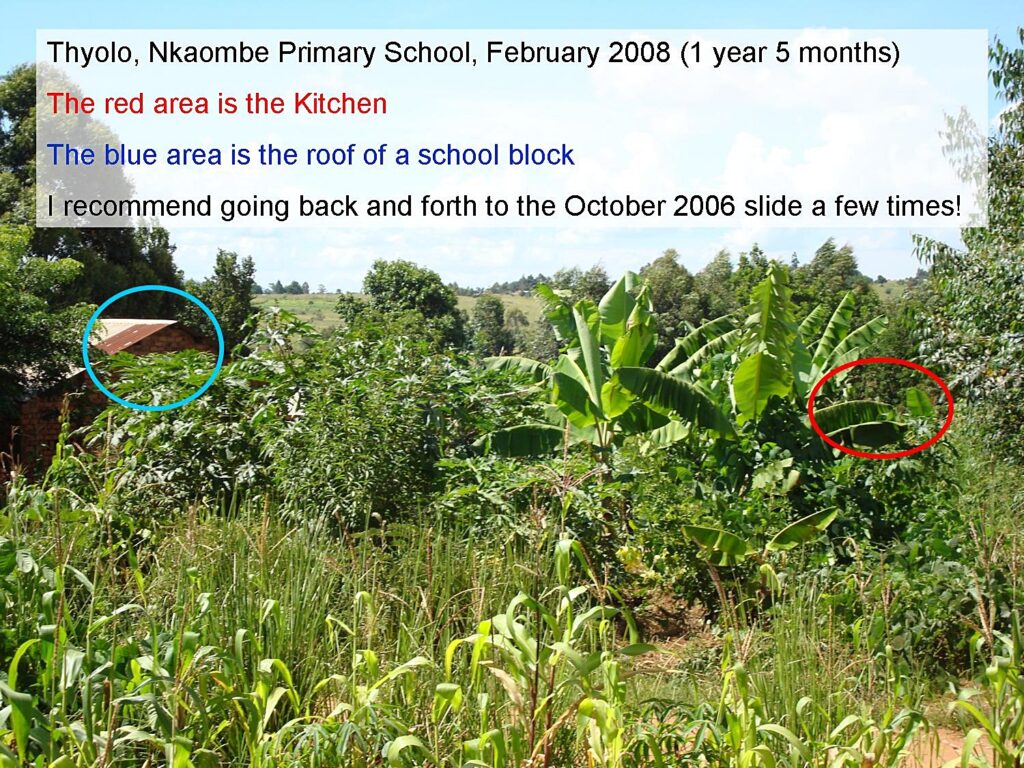

School 1: Nkaombe Primary School

The following sets of pictures are from October 2006, June 2007, and April 2008. The first set are just the picture, the second set has captions describing them to help show the fixed points in each picture – it gets hard to believe that the pictures are taken in the same place with all the plants and trees!

This school caught onto the idea of Permaculture immediately. In the initial school half-day sensitizations in July 2006, they went back to their school and start to apply the ideas. By October 2006 when we held the first workshops, this school already brough experience to the table – amazing people are at that school!

They organized themselves by class and village so that each area of the school had a group in charge of its design and maintenance – these really helps to break up big bare peices of earth into smaller, more manageable pieces. The head master and and the Teacher Permaculture Faciliator were strong forces of change and implemented everything at their homes. Positive role models are extremely valuable in the process of change.

School 2: Thunga TDC, Primary and Secondary

A Teacher Development Centre is a central point for 10-15 primary schools (the previous story of Nkaombe is of a school that is supported by Thunga TDC). At the TDC there is a Primary Education Advisor who supports primary school teachers to improve their access to resources, knowledge and skills. Teachers use the TDC for meetings, reporting and learning. The end result of this aims at improved learning environments for the children and the parents / community members who are involved in the school.

This picture is of Thunga TDC in October 2006 (with the secondary school in the background, not directly involved in the pilot, but who has started copying the work at the TDC and has joined in on the planning and coordination committee’s work). It takes a lot of work to keep a TDC looking like this! Daily sweeping of the grounds takes 20 people 30 minutes every day which is 10 hours of people labour every day. For the school year there are 180 school days which is 1,800 hours a year of work (or 225 working days – that’s a lot of time and energy wasted!).

The TDC committee and community had a hard time starting up and catching on to the ideas in the programme. Many still thought there were going to be ‘handouts’ provided such as tools, seeds, money, etc. The few that got the idea tried to develop the land, but those that didn’t get it worked directly against the progress.

Something finally changed about a year after the programme started (October 2006 was the first workshop, they came around in about October 2007). Once the TDC committee and community were all on the same page, they were able to work wonders in a short amount of time.

This picture shows the result of the committees work from October 2007 to February 2008 (5 months). How did they manage this? First, working together towards the same vision. Next, taking a close look at all the resources they had available to them. Then, creating a design based on their resources, their vision and the realities of the climate and geography where they are located. Finally, implementing the design, adapting it as needed along the way and Viola! improved environment, food and money.

The TDC has a market just 100 meters from where they are and they took advantage of all the organic matter, including seeds, that get swept into piles there. Instead of leaving the resource wasted, they collected the piles of organic matter and made it into rich planting beds. When the rainy season came in December, their land was ready to grow – and grow it did!

They now are able to harvest vegetables daily, some for eating and some for sale back to the market. Data on the estimated amounts harvested are coming in from the schools in April and May, so in the future we hope to share more concrete estimates with you. But, we know this – the land is producing where it wasn’t producing before, all because of a shift in mindset and using the resources that were previously wasted.

2020 update

Although Stacia no longer work directly with schools, she stays in touch with two key networks that support SHN, who both have Facebook Pages:

In addition, there is an organization in Malawi who works full time supporting Permaculture in Schools:

- Scope Malawi – Schools and Colleges Permaculture Programme – located in many districts throughout Malawi and also have a regional chapter. Scope’s origins are from Zimbabwe, and provided some of the learning for Malawi’s start up: 40 people from Malawi visited Scope Zimbabwe and some staff in the Ministry of Education attended a Permaculture certification course in Zimbabwe.

All donations go directly towards helping to spread Permaculture solutions throughout Malawi. Every little bit helps, and even a little can go a long way!